Your Pain, My Pleasure

Discovering the alluring links between pleasure and pain.

By Ena Dahl • 10 min read

Discovering the alluring links between pleasure and pain.

By Ena Dahl • 10 min read

Sex should be a perfect balance of pain and pleasure. Without that symmetry, sex becomes a routine rather than an indulgence.

— Marquis de Sade

What’s the link between pain with pleasure, and why do some enjoy certain types of pain more than others? Further, why can something feel painful in one setting and pleasurable in another?

To many, especially those who are strangers to sadomasochism, the idea of seeking pain for the sake of sexual arousal and satisfaction might seem foreign, even off-putting, but, if we look at how our brains are wired, there are natural explanations why us BDSM aficionados (and many others) indulge in the perplexing pleasures of pain.

Seeking pain for the sake of pleasure isn’t all that uncommon. Runners high, experienced by athletes and runners as the pain of physical exertion eclipses into pleasure, is a well-known phenomenon. Its gratification is further magnified with the promise of reward, such as completing and potentially winning a marathon. Similar highs can be derived through everything from excessive chili eating to receiving hot or painful massages, or from being tattooed or pierced.

While not necessarily painful, watching terrifying horror movies, riding rollercoasters, para shooting, and other extreme sports are examples of situations where we humans seek uncomfortable or scary scenarios in the name of entertainment or enjoyment.

Try to throw a dog off of a plane in a para shoot, or send them down a rollercoaster and you’ll see them be scared for their lives — and they would never voluntarily go for a second round. Humans, on the other hand, with our ability to understand and rationalize the situations, might seek out these thrills, again and again.

In this BBC article on why pain feels good, Paul Rozin, from the University of Pennsylvania claims that pain is a uniquely human indulgence: “Generally, when an animal experiences something negative, it avoids it.” He explains that while rats and other animals have been trained to self-inflict incentivized pain, meaning they do it if they receive a reward thereafter, humans are the only species on earth known to derive pleasure from the actual pain itself. The reasons behind this are partially found in our biology.

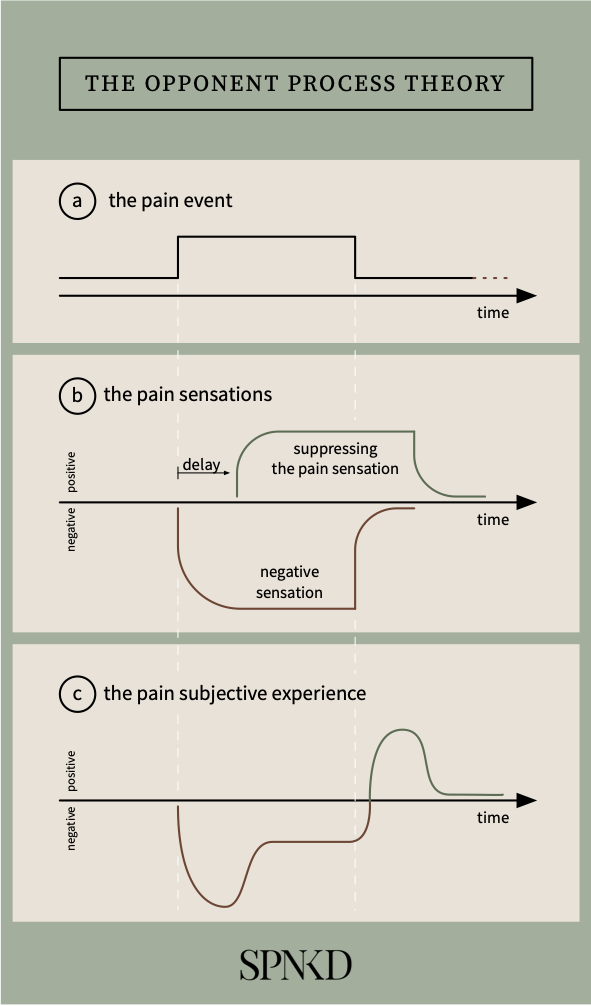

The pleasurable post-pain rush caused by a number of chemicals produced by the body’s nervous system is thought to have evolved to help us cope with the immediate aftermath of an injury, perhaps to aid us in escaping the potentially dangerous or life-threatening situations that caused the injury in the first place. This concoction of euphoria, bliss, and thrill is also the reason why pain can feel oh-so-good.

When we experience pain, our hippocampus, the nervous system’s control center, kicks in and responds by ordering the secretion of endorphins, our body’s natural narcotics. Beyond blocking the pain, these stimulate the brain’s limbic and prefrontal regions—the same areas that are activated when we experience pleasure, such as that of music, or an intense love affair. The rush feels similar to the high of opiates and explains the benign masochist’s post-pain euphoria after a good spanking.

Some types of pain also cause a spike in anandamide, another natural painkiller referred to as the bliss chemical. This binds to the cannabinoid receptors in the brain and induces the warm, fuzzy pleasure emulated by marijuana.

On top, pain also causes the production of adrenaline, thus adding to the excitement by raising our heart rate.

Pain is known to make us more sensitive, and, the sensualists and sensation seekers among us know to exploit this to our benefit. By activating our bodies, pain has the ability to elevate our senses to produce heightened experiences.

Using chili-eating as an example, these spicy capsicums cause temporary inflammation of the mucus membranes in the mouth, making it more sensitive. With our senses sharpened, the experience of eating can therefore become enhanced, taking it from a mundane activity to and intense and sensual one.

The great object of life is sensation, to feel that we exist, even though in pain.

— Lord Byron

Studies using fMRI to visualize the brains of women as they orgasm have found that over thirty areas of the brain were active, including those involved in registering pain. We see that the pain and pleasure centers in the brain are related and overlap.

The inability to experience pain, therefore, prohibits us from experiencing pleasure. This has been observed in cancer patients who’ve had spinal nerves severed to relieve suffering, but were to be unable to have orgasms after recovery. First once their nerves were mended were they able to fully enjoy sex again.

It makes perfect sense that medication and substances that numb our pain also numb our enjoyment—they are both sensations after all. Many may have noticed this by default; that those two ibuprofens they popped to dull a headache or the one-too-many glasses of wine made it harder to reach orgasm.

Certain elements and conditions must be present in order for pain to be experienced as pleasurable. Cause and context are the main denominators here: Why are we experiencing the pain? What’s causing it? Is the pain a sign of danger or are we safe?

Evolutionary psychology teaches us that, as a means of survival, humans are wired to be pleasure-seeking and pain avoiding; pain is our senses warning us that something is dangerous or bad for us, such as when we touch a hot cooking plate and automatically pull away to avoid getting burnt. Still, we are uniquely able to differentiate between good and bad pain.

If we experience a sudden toothache or an unexplained stabbing sensation in our chests, we’ll be alarmed and seek medical help. This is ‘bad pain’. If we, on the other hand, feel a dull ache in our hamstrings during yoga, or the intense sensation of a massage therapist pushing on a knot behind our shoulder blades, we’ll sigh in relief, despite our discomfort. Here we know that the pain is not a sign that something is wrong, but rather the opposite. This is ‘good pain’.

One of the differences between the scenarios above is anticipation; when we expect the pain, know the reason behind—when we know it’s not harming us, and perhaps even doing us good, such as in the case of a massage—we’re free to enjoy its pleasurable effects.

In the case of impact play, for example, laying propped up, waiting to receive a hard smack with a flogger will produce a very different result than if a random person came up and surprise-spanked us while sunbathing on the beach.

If the pain doesn’t frighten us; we’re not in real danger and we won’t be permanently injured, we’re less likely to experience a sensation as negative. In a sexual or BDSM context—when it’s the type of pain we’re expecting and have consented to, with someone we trust — we’re further allowed to savor and be aroused by it. Mutual trust and feeling safe are what sets the stage for a potentially pleasurable scene.

There are, of course, cases where safe pain is not experienced as pleasurable. Going back that toothache, we might feel safe once in the dentist’s chair and tolerate the pain because we know it will help us, but the vast majority will still dislike the sensations. Childbirth is another example of (relatively) safe pain that few women will describe as pleasurable. Again, it’s cause and context-based, and most importantly, there’s reward awaiting—which brings me to my last point:

When the pain is worth it, either because we receive an award after, or because we enjoy the pleasurable sensations of the pain itself, we have an incentive to endure it.

Our ancestors tolerated the strains of hunting for food, in knowing that the reward of consuming outgrew the discomfort of acquiring it. The birthing woman knows that holding her baby in her arms will be worth the pain.

In a BDSM setting, the act of receiving pain can become a part of the incentive itself, looping us back to biology and the hot-sauce of natural chemicals.

And painful pleasure turns to pleasing pain.

— Edmund Spenser

While pain is certainly physiological, as well as dependent on outside factors such as drugs and our overall physical state, pain, or the experience of it, is largely about mindset.

As someone who enjoys being on the submissive end of a D/s scenario, I know from experience that the same exact type or level of impact or other sensory play can be experienced differently depending on a multitude of factors; how safe I feel, how aroused I am, my personal feelings and relationship with my play partner, to mention a few. My own mental state or general mood can also alter my perception, and, in women especially, our hormonal cycles are yet another factor that plays a role.

Pain is relative, fluid, and multifaceted, and as long as we’re in safe hands, even when playing with danger, pain can be a powerful tool. As with all things BDSM, administering and receiving pain requires clear and open communication, but, when done right, it can both put us deeply in touch with our bodies as well as cause us to experience the utmost out-of-body ecstasy.

Sincerely,

Ena Dahl | Writer for SPNKD

MULTIDIMENSIONAL CREATRIX & MUSE

SEEKING TO UNITE SEXUALITY & SPIRITUALITY,

INSTIGATE ALCHEMICAL HEALING & IGNITE THE WILD (WO)MAN

ENADAHL.COM

Tips and resources to start your Kinbaku journey

By Tess Dagger • 9 min read • ENGLISH

Riggers and rope models share what Shibari means to them

By Ena Dahl • 9 min read • ENGLISH

By Tess Dagger • 7 min read • ENGLISH